This article is part of a series on Polaris best practices. Click here for more Community content or visit Anapedia for detailed technical guidance.

This article explores a technique to optimize calculations in Polaris. We examine the practice of including formula conditions directly (“inline”) in the formula itself to reduce calculation effort. This is possible because Polaris evaluates the entire formula to determine the most efficient calculation path — a behavior that becomes increasingly important as model dimensionality grows.

Overview

Splitting sub-expressions out into separate line items allows them to be shared, which can sometimes save work both from a performance and maintenance perspective. However, it also takes choices away from the engine, forcing it to fully calculate something it might have otherwise avoided doing.

In general, the guidance for Polaris is:

- Don't split sub-expressions out for no reason:

- If that sub-expression is shared by several calculations

(1), or surfaced in the UX, it might be a good option.

- If the expression has gotten too large to manage, splitting out sub-expressions might be reasonable.

- If you split out a sub-expression and it suddenly has a very large one-to-many Calculation Complexity (when the original expression didn't), put it back in-line with the original expression

(2).

When deciding whether to split out an expression in Polaris, keep this in mind: if you write something like <High-Dimensioned-But-Dense-Expression> * <Some-Sparse-Thing> as a single calculation, it will perform well because the engine can drive off the sparse element producing a sparse result. But if you move the dense expression into its own line item, the engine must evaluate it for every cell — an expensive operation due to its density.

Example

The key to understanding this is understanding a "cross" or “cross product”.

A "cross product” in a multi-dimensional context enumerates all the possible interactions of two (or more) things that are not actually related.

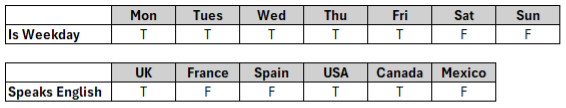

For example, consider two line-items:

- Is Weekday, which is TRUE for days of the week which are weekdays and

- Speaks English which is TRUE for countries whose primary language is English.

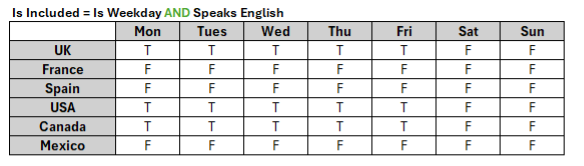

Let's imagine we create a line-item Is Included with the formula: Is Weekday AND Speaks English. This line-item is combining two unrelated pieces of information: every country and day pair where the country speaks English and the day is a weekday. The only way the engine can do this is to combine all the possibilities (in set theory this would be the cartesian product of the two sets, written Is Weekday x Speaks English).

Because Is Included has been given its own line item, the engine is forced to calculate every cell in that line item: evaluating every possible interaction of the two independent things.

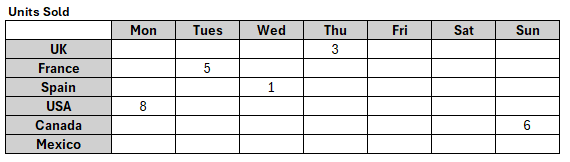

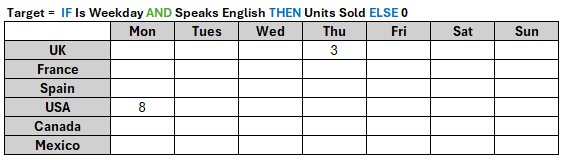

However, instead let’s imagine we have a line item Target with the formula: IF Is Weekday AND Speaks English THEN Units Sold ELSE 0, where both Target and Units Sold are dimensioned by Country and Day.

Units Sold looks like this (zeros shown blank):

And Target looks like this:

The engine can calculate the Target by walking through all the Units Sold that have non-default values and filtering out the ones that are either not on a weekday, or for a country that doesn't speak English. This means the engine does not have to evaluate every possible interaction of Is Weekday and Speaks English: it only needs to evaluate those specific interactions where Units Sold is not zero. There are much fewer of those compared to all the cells in Is Included, so this is a much more efficient approach.

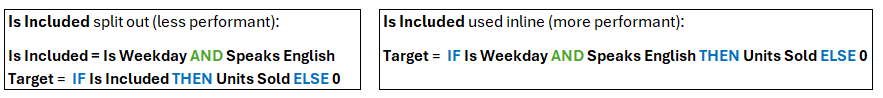

However, the engine can only take this approach if the formula for Is Included is used inline when calculating Target, rather than being split out. If it is pulled out into its own line item, as in Is Included, then the engine will have to evaluate every possible combination because that is what the user has asked for.

In summary, because of the powerful way Polaris can evaluate an expression in its entirety it may be more performant to include all logic within a formula, rather than splitting it out into separate line items as is best practice in Classic. However, the decision should be driven by the Calculation Complexity column: if splitting something out makes the calculation complexity for the new line item much higher than the original, then it's not a good idea. Conversely if it has the same (or less) calculation complexity it's fine to split it out.

……………..

(1) Repeating an expression within a single formula, while unnecessary, is not a reason to consider splitting it out. In Polaris, repeated expressions within the same formula are only calculated once and thus are unnecessary and they do not contribute to performance as they would in Classic. We encourage limiting repetition in this case to enhance maintenance and readability.

(2) This guidance differs from the approach used in Classic, but the Planual rule can be flexible in this context. If multiple line items could benefit from the repeated element, or if the formula is too complex, following the Planual recommendation to split it out may still be the best choice for model maintenance and auditability. However, be aware that this could negatively impact performance.

……………..

Author: Anaplan’s Theresa Reid (@TheresaR), Performance and Architecture Director.

Special thanks to Rob Marshall (@rob_marshall), Mark Warren (@MarkWarren), and Tom Shackell (@TomS) for their contributions.